1.GLOBAL E-WASTE TRADE AND THE

CASE OF AGBOGBLOSHIE

CASE OF AGBOGBLOSHIE

Portraying the Global E-waste Trade: Some Legal and Economic Aspects

By Lydia Karazarifi

Broken old machines, small devices taken apart, cables and the remains of hard drives in a vast area of broken materials. There are dim fires here and there. Women, men, children and animals are roaming around this place. Some of them work with these materials and others even play football in this landscape of smoke and e-waste. These are some of the images in the visual portrait of David Fedele “E-waste-land” (2012) that takes place in an e-waste dump in Ghana. He depicts life without using a lot of words. The images, sounds and movements give an adequate sense of what is going on. Yet, how and from where did these damaged and toxic materials come into places like this, and why?

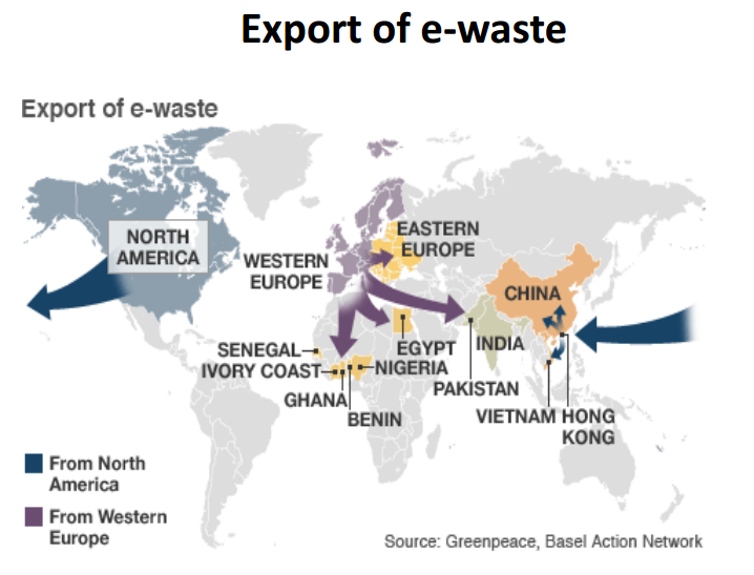

According to Basel Convention (1989), « e-waste that contains hazardous elements may not be exported to developing countries for disposal » (Lubick 2012; Marques 2020). Hazardous waste elements include industrial, commercial, mining and agricultural products that can damage the human health and the environment (Critharis 1990). Although a great number of countries have signed this legal agreement, the illegal circulation of toxic e-waste materials continue with high rates from the countries of Global North to Global South and mainly to countries of the African and Asian continent. Notably, around “50m tonnes of e-waste are generated globally each year, with only around 20% of it officially recycled” (Harris 2020) and although the big manufacturers have the adequate financial capital and infrastructures for recycling processes, they prefer to send the e-waste products to the developing countries and subsequently retrieve some of the raw materials of higher value, which they import from the countries of the Global South (Schmidt 2006).

One the other hand, Lubick (2012) argues that it is difficult to control the export of these e-waste products because of their quantity and status as ‘second hand’ goods. Besides, in some cases, countries that are heavily affected by the e-waste industry, rely on the potentially harmful industry in the form of informal recycling as a source of income, which maintains their livelihood. Yet, Charles W. Schmidt (2006) notes that only a small percentage of the e-waste materials can be used, which for instance in Nigeria is around 25% and the other 75% ends up as rubbish polluting the land and leading to health problems or even deaths of many inhabitants.

All in all, as Mary Critharis notes, “international waste trading is a business” (1990:314) and as we can understand in our time the notion of investments and profitable, super-growth economies are located at the centrum of the mainstream living management despite the overall costs of health insecurity and environmental precarity. However, this issue as any other social and environmental issue is complex and needs a profound understanding of adequate sustainable strategies. Yet, what is the cost of the centralization of the profit without social justice and welfare? And what is needed to deconstruct this paradigm of non-care and to create a landscape of care?

For more poetic stimuli regarding the e-waste management and resilience of local populations in Ghana, you can explore Donal O'Regan's creative contribution to the blog.

Bibliography:

Critharis, Mary (1990) "Third World Nations are Down in the Dumps: The Exportation of Hazardous Waste," Brooklyn Journal of International Law, vol. 16(2): pp. 311-340.

Fedele, David (2012) E-waste-land. Independent Production. URL: http://www.david-fedele.com/E-WASTELAND_files/HOME.html

Harris, John. Planned obsolescence: the outrage of our electronic waste mountain (Apr 2020) The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/15/the-right-to-repair-planned-obsolescence-electronic-waste-mountain

Lubick, Naomi (2012) “Shifting mountains of electronic waste.” Environmental health perspectives, vol. 120 (4): pp. A148-149. DOI:10.1289/ehp.120-a148

Marques, Luis (2020) Capitalism and Environmental Collapse. Springer (eBook). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47527-7

Schmidt, Charles W. (2006) Unfair Trade e-Waste in Africa. Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 114(4): pp. A232-A235. URL: https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.114-a232

Critharis, Mary (1990) "Third World Nations are Down in the Dumps: The Exportation of Hazardous Waste," Brooklyn Journal of International Law, vol. 16(2): pp. 311-340.

Fedele, David (2012) E-waste-land. Independent Production. URL: http://www.david-fedele.com/E-WASTELAND_files/HOME.html

Harris, John. Planned obsolescence: the outrage of our electronic waste mountain (Apr 2020) The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/15/the-right-to-repair-planned-obsolescence-electronic-waste-mountain

Lubick, Naomi (2012) “Shifting mountains of electronic waste.” Environmental health perspectives, vol. 120 (4): pp. A148-149. DOI:10.1289/ehp.120-a148

Marques, Luis (2020) Capitalism and Environmental Collapse. Springer (eBook). URL: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-47527-7

Schmidt, Charles W. (2006) Unfair Trade e-Waste in Africa. Environmental Health Perspectives, vol. 114(4): pp. A232-A235. URL: https://doi.org/10.1289/ehp.114-a232

http://www.cultofmac.com/390495/ghana-global-problem-e-waste-consequences/

Piles of circuit boards removed from electronics, Basel Action Network

MAKING POSSIBILITIES IN CAPITALIST RUINS: CASE STUDY OF E-WASTE IN AGBOGBLOSHIE, GHANA

by Jana Vanderkelen

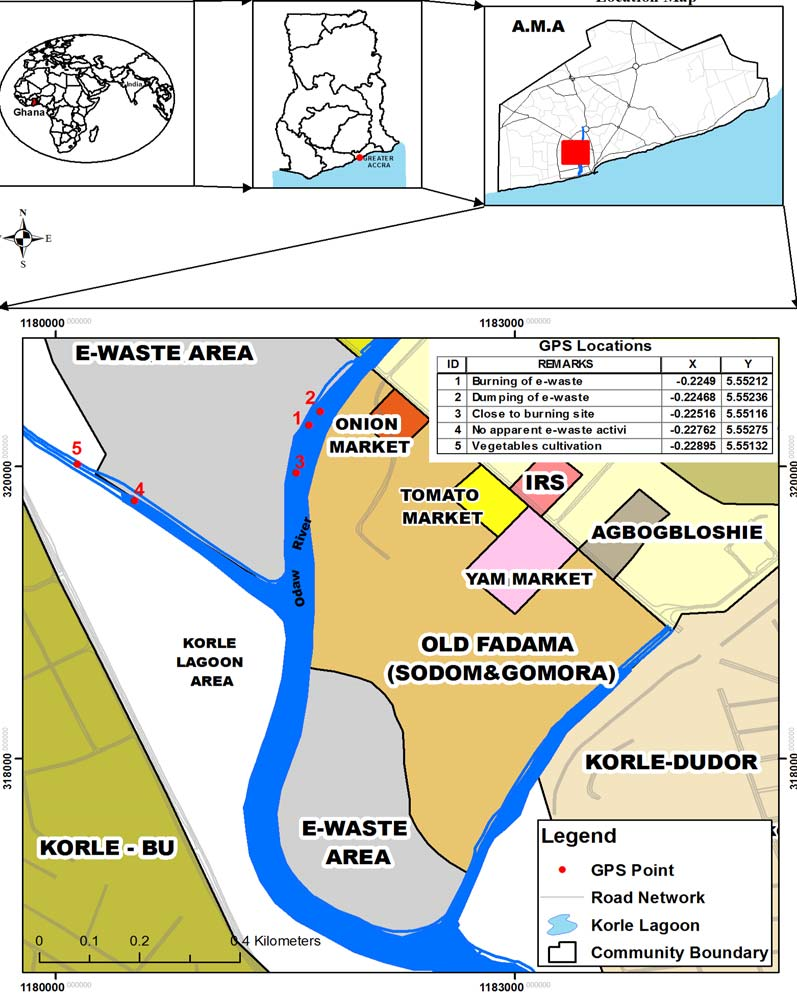

One of the largest e-waste sites is Agbogbloshie, located in Ghana’s capital city of Accra (Asante, et al. 2016). Agbogbloshie has become the primary destination for electrical and electronic goods imported from Europe and North America (Asante, et al. 2016). As a consequence of the increasing amount of e-waste exports from industrialized countries in the North, Agbogbloshie developed a large-scale informal e-waste recycling sector (Yang, et al. 2020). There are growing concerns about exposure to toxic chemicals and consequently to health problems due to the e-waste recycling process (Heacock, et al. 2016).

The problems associated with Agbogbloshie raise the question of environmental injustice. Agbogbloshie is one of the most polluted places on Earth (Akese en Little 2018). The claim of environmental injustice in Agbogbloshie finds its central referent in assertions that poor and marginalized populations in the global south are poisoned with toxic substances as they process the discards of rich countries in the global north (Akese en Little 2018). This statement is correct, but the injustices don’t only have environmental roots; they are also intertwined with socio-economic development.

Moreover, it sketches an image of the people of Agbogbloshie as passive actors, when this is not the case. Agbogbloshie is an example of Foucault’s Heterotopia: the phenomenon that outlines liminal social spaces in a city (Foucault 1984). In those spaces 'something else' is possible, which arises without a conscious plan, organically, influences how they shape their daily lives. Because people live like this all over the city, heterotopic spaces are created. Agbogbloshie is also an example of the urban poor fight in the notion of David Harvey (Harvey 2008) for the ‘right to the city’: this is enforced by the emergence of places like Abogbloshie where people can make a living in the informal trade and recycling process of E-waste.

Furthermore is the current polluted landscape of Agbogbloshie entangled in Ghana’s colonial history (Akese en Little 2018). The colonial economy kept the north of Ghana “underdeveloped”. There was more investment put into the infrastructure and labor in the gold mines and cocoa farms in the south (Akese en Little 2018). People from the North could no longer live happily due to the “underdevelopment” of northern Ghana; they sought a better quality in life in the South and consequently ended up in the informal sector of Agbogbloshie (Oteng-Ababio 2012).

As a matter of fact, raw materials scavenging in the informal E-waste economy as a livelihood strategy can be seen as a direct response to rapid urbanization, neoliberal globalization and a lack of formal job opportunities (Oteng-Ababio 2012). This persisting informal sector continues to displace the marginalized population. The real fundamental injustice lies therefore in socio-economic injustice, whereby Agbogbloshie exists in a postcolonial space (Akese en Little 2018).

Above all, resilience arises in many different forms. The resilience we see here is not resistance, but adaptation. People can make a living in the community as they continue to live under the threat of impending demolition expressed continuously by the city’s authority even as they rebuild the scrapyard (Akese en Little 2018). These workers are resilient because of how they create ‘possibilities in capitalist ruins (Tsing 2015). They live in a precarious environment, they work with what is available. They succeed in making a living, and to live in one of the most polluted places on Earth.

One of the largest e-waste sites is Agbogbloshie, located in Ghana’s capital city of Accra (Asante, et al. 2016). Agbogbloshie has become the primary destination for electrical and electronic goods imported from Europe and North America (Asante, et al. 2016). As a consequence of the increasing amount of e-waste exports from industrialized countries in the North, Agbogbloshie developed a large-scale informal e-waste recycling sector (Yang, et al. 2020). There are growing concerns about exposure to toxic chemicals and consequently to health problems due to the e-waste recycling process (Heacock, et al. 2016).

The problems associated with Agbogbloshie raise the question of environmental injustice. Agbogbloshie is one of the most polluted places on Earth (Akese en Little 2018). The claim of environmental injustice in Agbogbloshie finds its central referent in assertions that poor and marginalized populations in the global south are poisoned with toxic substances as they process the discards of rich countries in the global north (Akese en Little 2018). This statement is correct, but the injustices don’t only have environmental roots; they are also intertwined with socio-economic development.

Moreover, it sketches an image of the people of Agbogbloshie as passive actors, when this is not the case. Agbogbloshie is an example of Foucault’s Heterotopia: the phenomenon that outlines liminal social spaces in a city (Foucault 1984). In those spaces 'something else' is possible, which arises without a conscious plan, organically, influences how they shape their daily lives. Because people live like this all over the city, heterotopic spaces are created. Agbogbloshie is also an example of the urban poor fight in the notion of David Harvey (Harvey 2008) for the ‘right to the city’: this is enforced by the emergence of places like Abogbloshie where people can make a living in the informal trade and recycling process of E-waste.

Furthermore is the current polluted landscape of Agbogbloshie entangled in Ghana’s colonial history (Akese en Little 2018). The colonial economy kept the north of Ghana “underdeveloped”. There was more investment put into the infrastructure and labor in the gold mines and cocoa farms in the south (Akese en Little 2018). People from the North could no longer live happily due to the “underdevelopment” of northern Ghana; they sought a better quality in life in the South and consequently ended up in the informal sector of Agbogbloshie (Oteng-Ababio 2012).

As a matter of fact, raw materials scavenging in the informal E-waste economy as a livelihood strategy can be seen as a direct response to rapid urbanization, neoliberal globalization and a lack of formal job opportunities (Oteng-Ababio 2012). This persisting informal sector continues to displace the marginalized population. The real fundamental injustice lies therefore in socio-economic injustice, whereby Agbogbloshie exists in a postcolonial space (Akese en Little 2018).

Above all, resilience arises in many different forms. The resilience we see here is not resistance, but adaptation. People can make a living in the community as they continue to live under the threat of impending demolition expressed continuously by the city’s authority even as they rebuild the scrapyard (Akese en Little 2018). These workers are resilient because of how they create ‘possibilities in capitalist ruins (Tsing 2015). They live in a precarious environment, they work with what is available. They succeed in making a living, and to live in one of the most polluted places on Earth.

"Map showing the Agbogbloshie e-waste recycling site. Relative to the map of Agbogbloshie e-waste recycling site is the Accra Metropolitan Area (AMA) map where the study area is located. It also shows the map of Ghana and Africa. The site is located close to the Agbogbloshie food market (yam, onion, tomatoes)."

E-waste livelihoods, environment and health risk: Unpacking the connections in Ghana - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-showing-the-Agbogbloshie-e-waste-recycling-site-Relative-to-the-map-of-Agbogbloshie_fig1_306019229

E-waste livelihoods, environment and health risk: Unpacking the connections in Ghana - Scientific Figure on ResearchGate. Available from: https://www.researchgate.net/figure/Map-showing-the-Agbogbloshie-e-waste-recycling-site-Relative-to-the-map-of-Agbogbloshie_fig1_306019229

Bibliography:

Akese, Grace A., en Peter C Little. 2018. „Electronic Waste and the Environmental Justice Challenge in Agbogbloshie.” Environmental Justice 77-83.

Amankwaa, E. F. 2014. „E-waste Livelihoods, Environment and Health Risks: Unpacking the Connections in Ghana.” West African Journal of Applied Ecology 1-15.

Arain, A. L. , en R.L. Neitzel. 2019. „A review of biomarkers used for assessing human exposure to metals from E-waste.” Res Public Health.

Asante, Kwadwo Ansong, John A Pwamang, Yaw Amoyaw-Osei, en Joseph Addo Ampofo. 2016. „E-waste interventions in Ghana.” Rev Environmental Health 145-148.

Foucault, Michel. 1984. „Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias.” Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, 46-49.

Harvey, David. 2008. „The right to the city.” New Left Review, 23-40.

Heacock, Michelle, Carol Bain Kelly, Kwadwo Ansong Asante, Linda S Birnbaum, Ake

Lennart Bergman, Marie-Noel Bruné, Irena Buka, et al. 2016. „E-Waste and Harm to Vulnerable Populations: A Growing Global Problem.” Environ Health Perspect 550-555.

Oteng-Ababio, Martin. 2012. „When Necessity Begets Ingenuity: E-waste scavenging Livelihood Strategy in Accra, Ghana.” African Studies Quarterly 1-21.

Otsuka, M., T. Itaw, K.A. Asante, M. Muto, en S. Tanabe. 2012. „Trace element concentration around the e-waste recycling site at Agbogbloshie, Accra City, Ghana.” Interdisciplinary Studies on Environmental Chemistry and Environmental Pollution and Ecotoxicology, 161-167.

Srigboh, Roland Kofi , Niladri Basu, Judith Stephens, Emmanuel Asampong, Marie Perkins, Richard L. Neitzel, en Julius Fobil. 2016. „Multiple elemental exposures amongst workers at the Agbogbloshie electronic waste (e-waste) site in Ghana.” Chemosphere 68-74.

Sthiannopkao, Suthipong , en Ming Hung Wong. 2013. „Handling e-waste in developed and developing countries: Initiatives, practices, and consequences.” Science of Total Environment 463-464.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. „Mushroom at the end of the World: on the Possibilities of Life in Capitalist Ruins.” 352. United States: Princeton University Press.

Akese, Grace A., en Peter C Little. 2018. „Electronic Waste and the Environmental Justice Challenge in Agbogbloshie.” Environmental Justice 77-83.

Amankwaa, E. F. 2014. „E-waste Livelihoods, Environment and Health Risks: Unpacking the Connections in Ghana.” West African Journal of Applied Ecology 1-15.

Arain, A. L. , en R.L. Neitzel. 2019. „A review of biomarkers used for assessing human exposure to metals from E-waste.” Res Public Health.

Asante, Kwadwo Ansong, John A Pwamang, Yaw Amoyaw-Osei, en Joseph Addo Ampofo. 2016. „E-waste interventions in Ghana.” Rev Environmental Health 145-148.

Foucault, Michel. 1984. „Of Other Spaces, Heterotopias.” Architecture, Mouvement, Continuité, 46-49.

Harvey, David. 2008. „The right to the city.” New Left Review, 23-40.

Heacock, Michelle, Carol Bain Kelly, Kwadwo Ansong Asante, Linda S Birnbaum, Ake

Lennart Bergman, Marie-Noel Bruné, Irena Buka, et al. 2016. „E-Waste and Harm to Vulnerable Populations: A Growing Global Problem.” Environ Health Perspect 550-555.

Oteng-Ababio, Martin. 2012. „When Necessity Begets Ingenuity: E-waste scavenging Livelihood Strategy in Accra, Ghana.” African Studies Quarterly 1-21.

Otsuka, M., T. Itaw, K.A. Asante, M. Muto, en S. Tanabe. 2012. „Trace element concentration around the e-waste recycling site at Agbogbloshie, Accra City, Ghana.” Interdisciplinary Studies on Environmental Chemistry and Environmental Pollution and Ecotoxicology, 161-167.

Srigboh, Roland Kofi , Niladri Basu, Judith Stephens, Emmanuel Asampong, Marie Perkins, Richard L. Neitzel, en Julius Fobil. 2016. „Multiple elemental exposures amongst workers at the Agbogbloshie electronic waste (e-waste) site in Ghana.” Chemosphere 68-74.

Sthiannopkao, Suthipong , en Ming Hung Wong. 2013. „Handling e-waste in developed and developing countries: Initiatives, practices, and consequences.” Science of Total Environment 463-464.

Tsing, Anna Lowenhaupt. 2015. „Mushroom at the end of the World: on the Possibilities of Life in Capitalist Ruins.” 352. United States: Princeton University Press.

E-Waste Trade Through the Lens of Environmental Injustice and Racial Capitalism

By Lydia Karazarifi

As we have seen in the previous blog post “Global E-waste Trade: Legal and Economic Dimensions”, huge quantities of hazardous materials end up in the countries of Global South every year, increasing the global environmental injustice and health insecurity of the local populations. However, I wonder what the mentality behind these practices of global e-waste trade is and which factors accelerate this global environmental inequality between the Global South and North. Perhaps, by deconstructing this phenomenon and understanding it with anthropological lenses, we can comprehend our response-abilities in a sense of responsibility and new possibilities of action.

Historically, the roots of capitalism stem from the exploitation by European colonies in the Global South (Burden-Stelly 2020) especially that of their lucrative natural resources. Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2020) notes that “capitalism requires inequality and racism ensures it”. In this sense, the social constructions of race and racism constitute the preconditions of capitalism. Unequal access to environmental rights leads to geographies of racial capitalism, which often create a social disparity between the Global North and Global South in terms of environmental injustice. Often neoliberal policies of debt and austerity renew the colonial condition of order and global hierarchies and lead to the construction of neo-colonial regimes (Douzinas 2013) that perpetuate the global inequalities and environmental injustice. In the case of e-waste, as mentioned above, countries with the lowest economic statuses known as developing countries, accept the majority of the e-waste, which is characterized by toxic and hazardous materials. This fact underlines the unequal relations and the geographies of racial capitalism based on this binary of the exploitation among the geographies and people who are exploitable and the ones that are not.

On the other hand, the goal of capitalist regimes being eternal growth and profit, increases environmental injustice, by worsening the problem of e-waste accumulation in this case. The large manufacturers in this industry have implemented programs such as planned obsolescence limiting the lifespan of electronic devices to some months or a few years thus to increase the consumption of new and replaceable products (Harris 2020; Guiltinan 2009). The mindset of overconsumption has a great impact on the environment and people’s lives in terms of toxicity and acceleration of climate change. Notably, climate change according to Mohai et al (2009) worsens the relations of inequality in terms of environmental justice and the access to a healthy environment.

In conclusion, global e-waste trade is a current and global matter that illustrates the need for ethics and responsibility. Ethics in terms of consumption, marketing and decolonization, and responsibility in terms of action and demand for policies and livelihoods directed to fair environmental conditions. This need has become more apparent in our time, whereby new technologies and the increased use of digital mediums play a great role in our life and environmental problems have become more preoccupying. I choose to end this text with the words of Ruth Wilson Gilmore (2020), hoping for a more fair future in terms of environmental justice and well-being:

Bibliography:

Burden-Stelly, Charisse (2020) “Modern U.S. Racial Capitalism” in Monthly Review, vol. 72 (3): pp.8-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-072-03-2020-07_2

Douzinas, Costas (2013) Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis: Greece and the Future of Europe (1st Edition). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson (2020) “Geographies of Racial Capitalism”. An Antipode Foundation Film. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CS627aKrJI

Guiltinan, Joseph (2009) Creative Destruction and Destructive Creations: Environmental Ethics and Planned Obsolescence. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 89(1): pp. 19-28. Springer. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40295074

Harris, John. Planned obsolescence: the outrage of our electronic waste mountain (Apr 2020) The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/15/the-right-to-repair-planned-obsolescence-electronic-waste-mountain

Mohai, Paul, Pellow, David , Roberts, J.. (2009). Environmental Justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources? Vol. 34(1): pp.405-430. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348

Burden-Stelly, Charisse (2020) “Modern U.S. Racial Capitalism” in Monthly Review, vol. 72 (3): pp.8-20. DOI: https://doi.org/10.14452/MR-072-03-2020-07_2

Douzinas, Costas (2013) Philosophy and Resistance in the Crisis: Greece and the Future of Europe (1st Edition). Cambridge: Polity Press.

Gilmore, Ruth Wilson (2020) “Geographies of Racial Capitalism”. An Antipode Foundation Film. URL: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2CS627aKrJI

Guiltinan, Joseph (2009) Creative Destruction and Destructive Creations: Environmental Ethics and Planned Obsolescence. Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 89(1): pp. 19-28. Springer. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40295074

Harris, John. Planned obsolescence: the outrage of our electronic waste mountain (Apr 2020) The Guardian. URL: https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2020/apr/15/the-right-to-repair-planned-obsolescence-electronic-waste-mountain

Mohai, Paul, Pellow, David , Roberts, J.. (2009). Environmental Justice. Annual Review of Environment and Resources? Vol. 34(1): pp.405-430. DOI: 10.1146/annurev-environ-082508-094348

China Recycling #12. E-Waste Sorting, Zeguo, Zhejiang Province, 2004. Photograph © Edward Burtynsky.

“Solidarity and radical dependency is about life and living together and living together in rather beautiful ways”.

https://elpais.com/especiales/2015/basura-electronica/