RACE IN THE CAPITALOCENE

NARRATIVES OF RESILIENCE AND RESISTANCE

INTRODUCTION

by Sathya De Grande + Caroline De Ridder

Imagine this: a climate disaster happens, a whole community is severely affected as their entire village has been flooded. Dramatic, as these climate disasters are often irreversible. Different forms of disasters happen to different communities worldwide on a daily basis, but how coincidental are these events and how arbitrary are these communities or places of disaster?

As Bonilla (2020) states, a disaster is rarely ever 'natural', it is socially produced and is the effect of ongoing processes of structural violence. The circumstances of social and environmental vulnerability of certain communities, isn't natural but produced by a racio-colonial power (Bonilla 2020). Above that, the effects of these disasters are sharpened by pre-existing racial, gender and class hierarchies (Bonilla 2020). If you consider 70% of the CO2-emissions between 1850 and 2016 are the responsibility of industrialized countries (Zack 2020), we can state that those who are already more likely to suffer from the consequences of climate change, are also the least responsible for the climate change that caused these disasters to happen in the first place (Thomas & Haynes 2020).

Not only are the people most affected from disasters the least responsible, they are also more likely to breathe polluted air, live next to toxic sites and suffer from health issues (Zack 2020 and Yeampierre 2020). Yeampierre goes further and says that these people are even more targeted by racial violence. Research shows that polluters select places for their activities with a high percentage of black people, so race is more likely to get touched by pollutants than poverty (Thomas & Haynes 2020). Also because racism is related to the availability of housing and access to government support, Black individuals are less equipped to withstand disasters (Zack 2020).

Globally, climate movements have long failed to understand the link with racial justice (Lakhani & Watts 2020), failed to understand that this link goes back to the time of colonialism, where extreme extraction began, fitting right in with capitalism (Yeampierre 2020). Climate change is a child of these extractions and actions of destruction, again targeting the same people who were already a victim of colonialism and further structural racism (Yeampierre 2020). Not only does climate injustice go way back in history, it is also widespread over the world. It is estimated that by 2050 there will be 200 million people forced to migrate due to climate changes (Avijit & Bhaswati 2020).

So imagine this: a disaster happened and you don't get security from your own government, nor from other countries. Is that fair? For Nowshin (2020) the only way to create climate justice, is acknowledging that racism and the climate crisis have the same roots. By recognizing their interconnectedness, the fights can intertwine by prioritizing human security and confronting policymakers with environmental racism. 'Communities of colour' need to be addressed in all kinds of climate pacts. (Zack 2020)

“I need you to understand that our inequality crisis is intertwined with the climate crisis. If we don’t work on both, we will succeed at neither.”

Bibiliography:

Avijit Mistri, Bhaswati Das. 2020. Environmental Change, Livelihood Issues and Migration: Sundarban Biosphere Reserve, India. Singapore : Springer Singapore : Imprint Springer.

Bonilla, Yarimar. 2020. "The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA." Political Geography, (Elsevier Ltd) 78: 102181.

Harvey, Fiona. 2020. "Covid-19 pandemic is 'fire drill' for effects of climate crisis, says UN official." The Guardian. 15 June. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/15/covid-19-pandemic-is-fire-drill-for-effects-of-climate-crisis-says-un-official.

Lakhani, Nina, Watts, Jonathan. 2020. "Environmental justice means racial justice, say activists." The Guardian, 18 june 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/18/environmental-justice-means-racial-justice-say-activists

Nowshin, Tonny. 2020. "We need to talk about racism in the climate movement." Climate Home News. 30 June, 2020. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/06/30/need-talk-racism-climate-movement/.

Sciaccaluga, Giovanni. 2020. International Law and the Protection of Climate Refugees. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Thomas, Adelle, Haynes, Rueanna. 2020. "Black Lives Matter: the link between climate change and racial justice." Climateanalytics, June 22, 2020. https://climateanalytics.org/blog/2020/black-lives-matter-the-link-between-climate-change-and-racial-justice/

Yeampierre, Elizabeth. 2020. "Unequal Impact: The Deep Links Between Racism and Climate Change." Yale School of the Environment, june 9, 2020. https://e360.yale.edu/features/unequal-impact-the-deep-links-between-inequality-and-climate-change

Zack, Jacob. 2020. "Environmental Racism and Climate Justice: The Racialized Climate Catastrophe." The Georgetown University Center for Security Studies, August 28, 2020. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2020/08/28/environmental-racism-and-climate-justice-the-racialized-climate-catastrophe/

Avijit Mistri, Bhaswati Das. 2020. Environmental Change, Livelihood Issues and Migration: Sundarban Biosphere Reserve, India. Singapore : Springer Singapore : Imprint Springer.

Bonilla, Yarimar. 2020. "The coloniality of disaster: Race, empire, and the temporal logics of emergency in Puerto Rico, USA." Political Geography, (Elsevier Ltd) 78: 102181.

Harvey, Fiona. 2020. "Covid-19 pandemic is 'fire drill' for effects of climate crisis, says UN official." The Guardian. 15 June. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/15/covid-19-pandemic-is-fire-drill-for-effects-of-climate-crisis-says-un-official.

Lakhani, Nina, Watts, Jonathan. 2020. "Environmental justice means racial justice, say activists." The Guardian, 18 june 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2020/jun/18/environmental-justice-means-racial-justice-say-activists

Nowshin, Tonny. 2020. "We need to talk about racism in the climate movement." Climate Home News. 30 June, 2020. https://www.climatechangenews.com/2020/06/30/need-talk-racism-climate-movement/.

Sciaccaluga, Giovanni. 2020. International Law and the Protection of Climate Refugees. Cham: Springer International Publishing AG.

Thomas, Adelle, Haynes, Rueanna. 2020. "Black Lives Matter: the link between climate change and racial justice." Climateanalytics, June 22, 2020. https://climateanalytics.org/blog/2020/black-lives-matter-the-link-between-climate-change-and-racial-justice/

Yeampierre, Elizabeth. 2020. "Unequal Impact: The Deep Links Between Racism and Climate Change." Yale School of the Environment, june 9, 2020. https://e360.yale.edu/features/unequal-impact-the-deep-links-between-inequality-and-climate-change

Zack, Jacob. 2020. "Environmental Racism and Climate Justice: The Racialized Climate Catastrophe." The Georgetown University Center for Security Studies, August 28, 2020. https://georgetownsecuritystudiesreview.org/2020/08/28/environmental-racism-and-climate-justice-the-racialized-climate-catastrophe/

(Lakhani & Watts 2020)

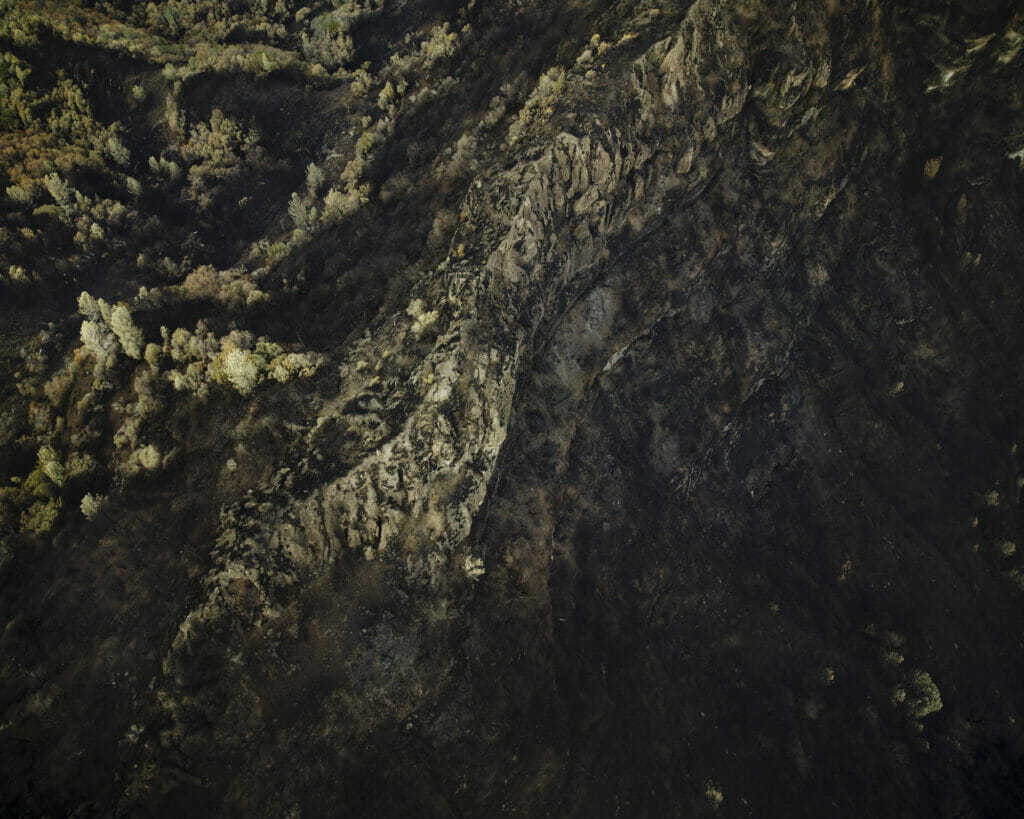

Photographs courtesy of Thomas Heinser Studios, Aerial Series

ABOUT

This blog uses case studies from disparate localities to demonstrate how "race" as a historical device for marking and governing difference figures in this era of Anthropogenic climate change. We understand climate change as a crisis instigated by global extraction and industrialization and upheld by the logics of domination, characteristic of contemporary capitalism and its biopolitics. We chose the title 'Race in the Capitalocene: narratives of resistance and resilience' as we want to make clear how this combination of capitalism and a nuanced version of the anthropocene -as not every single human equally attributes to global warming- causes racial inequalities when it comes to climate change. The "logics of domination" systematically exploit and disproportionately lay bare the livelihoods of People of Color, Indigenous, women, low-income, other-than-humans, and land, exposing them to exploitation and extermination.

In providing these specific case studies we intend to illustrate the systemic violence climate change makes visible. 'Resilience' is often promoted by governmental and international agencies, but who are these communities who have been historically required to always absorb and bounce back? Counting on their resilience is one of the problems at the basis of their disproportional vulnerability to climate change effects (Bonilla, 2020). We do however want to share these strategies of resistance and resilience as they testify to a complex and nuanced account of climate change sensitive to power, agency, and knowledge production. Resilience can be more or less visible, and as shown in the different cases it can take subtle forms in daily life.

Contributing Authors:

Sathya De Grande, Mehdi Firouzi, Mary Hogan, Caroline De Ridder, Sheila Tahir, Jana Vanderkelen, Donal O'Regan, Qi Gaofeng, Keesha Orts, Lydia Karazarifi, Andrey Smolyakov

Design: Mary Hogan

In providing these specific case studies we intend to illustrate the systemic violence climate change makes visible. 'Resilience' is often promoted by governmental and international agencies, but who are these communities who have been historically required to always absorb and bounce back? Counting on their resilience is one of the problems at the basis of their disproportional vulnerability to climate change effects (Bonilla, 2020). We do however want to share these strategies of resistance and resilience as they testify to a complex and nuanced account of climate change sensitive to power, agency, and knowledge production. Resilience can be more or less visible, and as shown in the different cases it can take subtle forms in daily life.

Contributing Authors:

Sathya De Grande, Mehdi Firouzi, Mary Hogan, Caroline De Ridder, Sheila Tahir, Jana Vanderkelen, Donal O'Regan, Qi Gaofeng, Keesha Orts, Lydia Karazarifi, Andrey Smolyakov

Design: Mary Hogan

Richard Misrach, from "Petrochemical America"

by Sathya De Grande + Caroline De Ridder

This section of the blog addresses the issue of ‘e-waste,’ in terms of its ecological effect on both the microscale and macroscale. Beginning with the macroscale; this section delves into the economic paradigm which has been created in accordance with the neoliberal practice of transporting ‘e-waste’ from the developed world, to developing countries. This leads to the questions surrounding the environmental and socioeconomic disparity, the concept of racial capitalism, and the debate surrounding the responsibility and ethics in terms of neoliberal practices. Furthermore, this section refers to the microscale example of Agbogbloshie, which is located in Ghana’s capital of Accra. This case illuminates the environmental injustice which occurs as a result of ‘e-waste.’ The socioeconomic inequality experienced in Agbogbloshie is emphasised by the lack of State intervention, which seemingly reveals a particular form of resilience which is displayed by the local community.

The focus of these blogposts revolves around a geographic area known as "Cancer Alley" in the Mississippi river adjacent parishes of Louisiana, USA. We will provide an account of the history of this site and its relationship with the trans-atlantic slave trade, petrochemical plants and unprecedented cancer rates. The trajectory from slavery to toxic pollution is marked by the systemic and continued exposure of Black bodies to harm. The concept of “toxicity” will be explored and considered as a way of reading affect, intimacies and proximities between bodies. Through the scholarship of Mel Chen we propose a queering of toxicity in order to render visible relations that happen outside hegemonic and heteronormative logics. On the ground activism and resilience will be illustrated through the voices of various residents of the region, many of whom are Black women involved in grassroots organizing.

This case study explores how “race” and biopolitics are played out in the occupied territories of Palestine, since water availability and quality is one of the biggest threats and key environmental and political challenges in this area. Water is a basic human right and the most important tool for survival in the ‘capitalocene’. Palestinians are deprived from clean water and have limited control and access to their natural resources, especially water (due to Israelian occupation). This case illustrates how the climate crisis can be understood as the result of a particular economic and political model, namely capitalism and settler colonialism, which is based on growth, extraction and exploitation.

KEY CONCEPTS